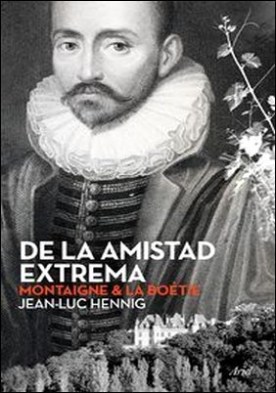

Ensayos Montaigne Libro 2 Pdf

Essays of Michel de MontaigneProject Gutenberg's The Essays of Montaigne, Complete, by Michel de MontaigneThis eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and withalmost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away orre-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License includedwith this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.netTitle: The Essays of Montaigne, CompleteAuthor: Michel de MontaigneRelease Date: September 17, 2006 EBook #3600Last Updated: August 8, 2016Language: EnglishCharacter set encoding: UTF-8. START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE ESSAYS OF MONTAIGNE, COMPLETE.Produced by David WidgerESSAYS OFMICHEL DE MONTAIGNETranslated by Charles CottonEdited by William Carew Hazlitt1877. PREFACEThe present publication is intended to supply a recognised deficiency inour literature—a library edition of the Essays of Montaigne. Thisgreat French writer deserves to be regarded as a classic, not only in theland of his birth, but in all countries and in all literatures.

HisEssays, which are at once the most celebrated and the most permanent ofhis productions, form a magazine out of which such minds as those of Baconand Shakespeare did not disdain to help themselves; and, indeed, as Hallamobserves, the Frenchman’s literary importance largely results fromthe share which his mind had in influencing other minds, coeval andsubsequent. But, at the same time, estimating the value and rank of theessayist, we are not to leave out of the account the drawbacks and thecircumstances of the period: the imperfect state of education, thecomparative scarcity of books, and the limited opportunities ofintellectual intercourse. Montaigne freely borrowed of others, and he hasfound men willing to borrow of him as freely. We need not wonder at thereputation which he with seeming facility achieved. He was, without beingaware of it, the leader of a new school in letters and morals.

His bookwas different from all others which were at that date in the world. Itdiverted the ancient currents of thought into new channels. It told itsreaders, with unexampled frankness, what its writer’s opinion wasabout men and things, and threw what must have been a strange kind of newlight on many matters but darkly understood. Above all, the essayistuncased himself, and made his intellectual and physical organism publicproperty. He took the world into his confidence on all subjects. Hisessays were a sort of literary anatomy, where we get a diagnosis of thewriter’s mind, made by himself at different levels and under a largevariety of operating influences.Of all egotists, Montaigne, if not the greatest, was the most fascinating,because, perhaps, he was the least affected and most truthful.

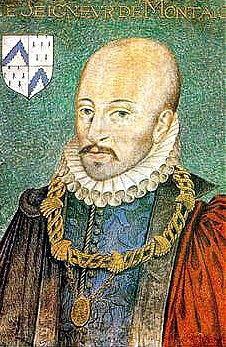

What hedid, and what he had professed to do, was to dissect his mind, and showus, as best he could, how it was made, and what relation it bore toexternal objects. He investigated his mental structure as a schoolboypulls his watch to pieces, to examine the mechanism of the works; and theresult, accompanied by illustrations abounding with originality and force,he delivered to his fellow-men in a book.Eloquence, rhetorical effect, poetry, were alike remote from his design.He did not write from necessity, scarcely perhaps for fame. THE LIFE OF MONTAIGNEThis is translated freely from that prefixed to the ‘variorum’Paris edition, 1854, 4 vols. This biography is the more desirablethat it contains all really interesting and important matter in thejournal of the Tour in Germany and Italy, which, as it was merely writtenunder Montaigne’s dictation, is in the third person, is scarcelyworth publication, as a whole, in an English dress.The author of the Essays was born, as he informs us himself, betweeneleven and twelve o’clock in the day, the last of February 1533, atthe chateau of St. Michel de Montaigne. His father, Pierre Eyquem,esquire, was successively first Jurat of the town of Bordeaux (1530),Under-Mayor 1536, Jurat for the second time in 1540, Procureur in 1546,and at length Mayor from 1553 to 1556. He was a man of austere probity,who had “a particular regard for honour and for propriety in hisperson and attire.

A mighty good faith in his speech, and aconscience and a religious feeling inclining to superstition, rather thanto the other extreme.' 2. Pierre Eyquem bestowed great careon the education of his children, especially on the practical side of it.To associate closely his son Michel with the people, and attach him tothose who stand in need of assistance, he caused him to be held at thefont by persons of meanest position; subsequently he put him out to nursewith a poor villager, and then, at a later period, made him accustomhimself to the most common sort of living, taking care, nevertheless, tocultivate his mind, and superintend its development without the exerciseof undue rigour or constraint.

Michel, who gives us the minutest accountof his earliest years, charmingly narrates how they used to awake him bythe sound of some agreeable music, and how he learned Latin, withoutsuffering the rod or shedding a tear, before beginning French, thanks tothe German teacher whom his father had placed near him, and who neveraddressed him except in the language of Virgil and Cicero. The study ofGreek took precedence. At six years of age young Montaigne went to theCollege of Guienne at Bordeaux, where he had as preceptors the mosteminent scholars of the sixteenth century, Nicolas Grouchy, Guerente,Muret, and Buchanan. At thirteen he had passed through all the classes,and as he was destined for the law he left school to study that science.He was then about fourteen, but these early years of his life are involvedin obscurity. The next information that we have is that in 1554 hereceived the appointment of councillor in the Parliament of Bordeaux; in1559 he was at Bar-le-Duc with the court of Francis II, and in the yearfollowing he was present at Rouen to witness the declaration of themajority of Charles IX.

We do not know in what manner he was engaged onthese occasions.Between 1556 and 1563 an important incident occurred in the life ofMontaigne, in the commencement of his romantic friendship with Etienne dela Boetie, whom he had met, as he tells us, by pure chance at some festivecelebration in the town. From their very first interview the two foundthemselves drawn irresistibly close to one another, and during six yearsthis alliance was foremost in the heart of Montaigne, as it was afterwardsin his memory, when death had severed it.Although he blames severely in his own book Essays, i. 27. those who,contrary to the opinion of Aristotle, marry before five-and-thirty,Montaigne did not wait for the period fixed by the philosopher of Stagyra,but in 1566, in his thirty-third year, he espoused Francoise deChassaigne, daughter of a councillor in the Parliament of Bordeaux.

Ensayos Montaigne Libro 2 Pdf Download

Thehistory of his early married life vies in obscurity with that of hisyouth. His biographers are not agreed among themselves; and in the samedegree that he lays open to our view all that concerns his secretthoughts, the innermost mechanism of his mind, he observes too muchreticence in respect to his public functions and conduct, and his socialrelations. The title of Gentleman in Ordinary to the King, which heassumes, in a preface, and which Henry II. Gives him in a letter, which weprint a little farther on; what he says as to the commotions of courts,where he passed a portion of his life; the Instructions which he wroteunder the dictation of Catherine de Medici for King Charles IX., and hisnoble correspondence with Henry IV., leave no doubt, however, as to thepart which he played in the transactions of those times, and we find anunanswerable proof of the esteem in which he was held by the most exaltedpersonages, in a letter which was addressed to him by Charles at the timehe was admitted to the Order of St.

Michael, which was, as he informs ushimself, the highest honour of the French noblesse.According to Lacroix du Maine, Montaigne, upon the death of his eldestbrother, resigned his post of Councillor, in order to adopt the militaryprofession, while, if we might credit the President Bouhier, he neverdischarged any functions connected with arms. However, several passages inthe Essays seem to indicate that he not only took service, but that he wasactually in numerous campaigns with the Catholic armies. I.——To Monsieur de MONTAIGNEThis account of the death of La Boetie begins imperfectly. It firstappeared in a little volume of Miscellanies in 1571. See Hazlitt, ubi sup.p.

630.—As to his last words, doubtless, if any man can give goodaccount of them, it is I, both because, during the whole of his sicknesshe conversed as fully with me as with any one, and also because, inconsequence of the singular and brotherly friendship which we hadentertained for each other, I was perfectly acquainted with theintentions, opinions, and wishes which he had formed in the course of hislife, as much so, certainly, as one man can possibly be with those ofanother man; and because I knew them to be elevated, virtuous, full ofsteady resolution, and (after all said) admirable. I well foresaw that, ifhis illness permitted him to express himself, he would allow nothing tofall from him, in such an extremity, that was not replete with goodexample. I consequently took every care in my power to treasure what wassaid.

True it is, Monseigneur, as my memory is not only in itself veryshort, but in this case affected by the trouble which I have undergone,through so heavy and important a loss, that I have forgotten a number ofthings which I should wish to have had known; but those which I recollectshall be related to you as exactly as lies in my power. For to representin full measure his noble career suddenly arrested, to paint to you hisindomitable courage, in a body worn out and prostrated by pain and theassaults of death, I confess, would demand a far better ability than mine:because, although, when in former years he discoursed on serious andimportant matters, he handled them in such a manner that it was difficultto reproduce exactly what he said, yet his ideas and his words at the lastseemed to rival each other in serving him. For I am sure that I never knewhim give birth to such fine conceptions, or display so much eloquence, asin the time of his sickness.

If, Monseigneur, you blame me for introducinghis more ordinary observations, please to know that I do so advisedly; forsince they proceeded from him at a season of such great trouble, theyindicate the perfect tranquillity of his mind and thoughts to the last.On Monday, the 9th day of August 1563, on my return from the Court, I sentan invitation to him to come and dine with me. He returned word that hewas obliged, but, being indisposed, he would thank me to do him thepleasure of spending an hour with him before he started for Medoc. Shortlyafter my dinner I went to him. He had laid himself down on the bed withhis clothes on, and he was already, I perceived, much changed.

Hecomplained of diarrhoea, accompanied by the gripes, and said that he hadit about him ever since he played with M. D’Escars with nothing buthis doublet on, and that with him a cold often brought on such attacks. Iadvised him to go as he had proposed, but to stay for the night atGermignac, which is only about two leagues from the town.

I gave him thisadvice, because some houses, near to that where he was ping, were visitedby the plague, about which he was nervous since his return from Perigordand the Agenois, here it had been raging; and, besides, horse exercisewas, from my own experience, beneficial under similar circumstances. Heset out, accordingly, with his wife and M.

Bouillhonnas, his uncle.Early on the following morning, however, I had intelligence from Madame dela Boetie, that in the night he had fresh and violent attack of dysentery.She had called in physician and apothecary, and prayed me to lose no timecoming, which (after dinner) I did. He was delighted to see me; and when Iwas going away, under promise to turn the following day, he begged me moreimportunately and affectionately than he was wont to do, to give him assuch of my company as possible. I was a little affected; yet was about toleave, when Madame de la Boetie, as if she foresaw something about tohappen, implored me with tears to stay the night. When I consented, heseemed to grow more cheerful. I returned home the next day, and on theThursday I paid him another visit. He had become worse; and his loss ofblood from the dysentery, which reduced his strength very much, waslargely on the increase. I quitted his side on Friday, but on Saturday Iwent to him, and found him very weak.

He then gave me to understand thathis complaint was infectious, and, moreover, disagreeable and depressing;and that he, knowing thoroughly my constitution, desired that I shouldcontent myself with coming to see him now and then. On the contrary, afterthat I never left his side.It was only on the Sunday that he began to converse with me on any subjectbeyond the immediate one of his illness, and what the ancient doctorsthought of it: we had not touched on public affairs, for I found at thevery outset that he had a dislike to them.But, on the Sunday, he had a fainting fit; and when he came to himself, hetold me that everything seemed to him confused, as if in a mist and indisorder, and that, nevertheless, this visitation was not unpleasing tohim. “Death,” I replied, “has no worse sensation, mybrother.” “None so bad,” was his answer. He had had noregular sleep since the beginning of his illness; and as he became worseand worse, he began to turn his attention to questions which men commonlyoccupy themselves with in the last extremity, despairing now of gettingbetter, and intimating as much to me. II.——To Monseigneur, Monseigneur de MONTAIGNE.This letter is prefixed to Montaigne’s translation of the “NaturalTheology” of Raymond de Sebonde, printed at Paris in 1569.In pursuance of the instructions which you gave me last year in your houseat Montaigne, Monseigneur, I have put into a French dress, with my ownhand, Raymond de Sebonde, that great Spanish theologian and philosopher;and I have divested him, so far as I could, of that rough bearing andbarbaric appearance which you saw him wear at first; that, in my opinion,he is now qualified to present himself in the best company.

It isperfectly possible that some fastidious persons will detect in the booksome trace of Gascon parentage; but it will be so much the more to theirdiscredit, that they allowed the task to devolve on one who is quite anovice in these things. It is only right, Monseigneur, that the workshould come before the world under your auspices, since whateveremendations and polish it may have received, are owing to you. Still I seewell that, if you think proper to balance accounts with the author, youwill find yourself much his debtor; for against his excellent andreligious discourses, his lofty and, so to speak, divine conceptions, youwill find that you will have to set nothing but words and phraseology; asort of merchandise so ordinary and commonplace, that whoever has the mostof it, peradventure is the worst off.Monseigneur, I pray God to grant you a very long and happy life. FromParis, this 18th of June 1568. Your most humble and most obedient son,MICHEL DE MONTAIGNE. III.——To Monsieur, Monsieur de LANSAC,—This letter appears to belong to 1570.—Knight of the King’sOrder, Privy Councillor, Sub-controller of his Finance, and Captain of theCent Gardes of his Household.MONSIEUR,—I send you the OEconomics of Xenophon, put into French bythe late M.

De la Boetie,—Printed at Paris, 8vo, 1571, andreissued, with the addition of some notes, in 1572, with a freshtitle-page.—a present which appears to me to be appropriate, aswell because it is the work of a gentleman of mark,—MeaningXenophon.—a man illustrious in war and peace, as because it hastaken its second shape from a personage whom I know to have been held byyou in affectionate regard during his life. This will be an inducement toyou to continue to cherish towards his memory, your good opinion andgoodwill. Roto hoe chipper parts list.

Ensayos Montaigne Libro 2 Pdf Gratis

And to be bold with you, Monsieur, do not fear to increase thesesentiments somewhat; for, as you had knowledge of his high qualities onlyin his public capacity, it rests with me to assure you how many endowmentshe possessed beyond your personal experience of him. He did me the honour,while he lived, and I count it amongst the most fortunate circumstances inmy own career, to have with me a friendship so close and so intricatelyknit, that no movement, impulse, thought, of his mind was kept from me,and if I have not formed a right judgment of him, I must suppose it to befrom my own want of scope. Indeed, without exaggeration, he was so nearlya prodigy, that I am afraid of not being credited when I speak of him,even though I should keep much within the mark of my own actual knowledge.And for this time, Monsieur, I shall content myself with praying you, forthe honour and respect we owe to truth, to testify and believe that ourGuienne never beheld his peer among the men of his vocation. Under thehope, therefore, that you will pay him his just due, and in order torefresh him in your memory, I present you this book, which will answer forme that, were it not for the insufficiency of my power, I would offer youas willingly something of my own, as an acknowledgment of the obligationsI owe to you, and of the ancient favour and friendship which you haveborne towards the members of our house. But, Monsieur, in default ofbetter coin, I offer you in payment the assurance of my desire to do youhumble service.Monsieur, I pray God to have you in His keeping. Your obedient servant,MICHEL DE MONTAIGNE.

V.——To Monsieur, Monsieur de L’HOSPITAL, Chancellor ofFranceMONSEIGNEUR,—I am of the opinion that persons such as you, to whomfortune and reason have committed the charge of public affairs, are notmore inquisitive in any point than in ascertaining the character of thosein office under you; for no society is so poorly furnished, but that, if aproper distribution of authority be used, it has persons sufficient forthe discharge of all official duties; and when this is the case, nothingis wanting to make a State perfect in its constitution. VII.——To Mademoiselle de MONTAIGNE, my Wife.—Printed as a preface to the “Consolation of Plutarch to hisWife,” published by Montaigne, with several other tracts by LaBoetie, about 1571.MY WIFE,—You understand well that it is not proper for a man of theworld, according to the rules of this our time, to continue to court andcaress you; for they say that a sensible person may take a wife indeed,but that to espouse her is to act like a fool. Let them talk; I adhere formy part the custom of the good old days; I also wear my hair as it used tobe then; and, in truth, novelty costs this poor country up to the presentmoment so dear (and I do not know whether we have reached the highestpitch yet), that everywhere and in everything I renounce the fashion. Letus live, my wife, you and I, in the old French method.

Now, you mayrecollect that the late M. De la Boetie, my brother and inseparablecompanion, gave me, on his death-bed, all his books and papers, which haveremained ever since the most precious part of my effects. I do not wish tokeep them niggardly to myself alone, nor do I deserve to have theexclusive use of them; so that I have resolved to communicate them to myfriends; and because I have none, I believe, more particularly intimateyou, I send you the Consolatory Letter written by Plutarch to his Wife,translated by him into French; regretting much that fortune has made it sosuitable a present you, and that, having had but one child, and that adaughter, long looked for, after four years of your married life it wasyour lot to lose her in the second year of her age. But I leave toPlutarch the duty of comforting you, acquainting you with your dutyherein, begging you to put your faith in him for my sake; for he willreveal to you my own ideas, and will express the matter far better than Ishould myself. Hereupon, my wife, I commend myself very heartily to yourgood will, and pray God to have you in His keeping. From Paris, this 10thSeptember 1570.—Your good husband,MICHEL DE MONTAIGNE. VIII.——To Monsieur DUPUY,—This is probably the Claude Dupuy, born at Paris in 1545, and oneof the fourteen judges sent into Guienne after the treaty of Fleix in1580.

It was perhaps under these circumstances that Montaigne addressed tohim the present letter.—the King’s Councillor in his Courtand Parliament of Paris.MONSIEUR,—The business of the Sieur de Verres, a prisoner, who isextremely well known to me, deserves, in the arrival at a decision, theexercise of the clemency natural to you, if, in the public interest, youcan fairly call it into play. He has done a thing not only excusable,according to the military laws of this age, but necessary and (as we areof opinion) commendable. He committed the act, without doubt, unwillinglyand under pressure; there is no other passage of his life which is open toreproach. I beseech you, sir, to lend the matter your attentiveconsideration; you will find the character of it as I represent it to you.He is persecuted on this crime, in a way which is far worse than theoffence itself. If it is likely to be of use to him, I desire to informyou that he is a man brought up in my house, related to severalrespectable families, and a person who, having led an honourable life, ismy particular friend. By saving him you lay me under an extremeobligation.

I beg you very humbly to regard him as recommended by me, and,after kissing your hands, I pray God, sir, to grant you a long and happylife. From Castera, this 23d of April 1580. Your affectionate servant,MONTAIGNE.

IX.——To the Jurats of Bordeaux.—Published from the original among the archives of the town ofBordeaux, M. Gustave Brunet in the Bulletin du Bibliophile, July 1839.GENTLEMEN,—I trust that the journey of Monsieur de Cursol will be ofadvantage to the town.

Having in hand a case so just and so favourable,you did all in your power to put the business in good trim; and mattersbeing so well situated, I beg you to excuse my absence for some littletime longer, and I will abridge my stay so far as the pressure of myaffairs permits. I hope that the delay will be short; however, you willkeep me, if you please, in your good grace, and will command me, if theoccasion shall arise, in employing me in the public service and in yours.Monsieur de Cursol has also written to me and apprised me of his journey.I humbly commend myself to you, and pray God, gentlemen, to grant you longand happy life. From Montaigne, this 21st of May 1582. Your humble brotherand servant, MONTAIGNE. X.——To the same.—The original is among the archives of Toulouse.GENTLEMEN,—I have taken my fair share of the satisfaction which youannounce to me as feeling at the good despatch of your business, asreported to you by your deputies, and I regard it as a favourable signthat you have made such an auspicious commencement of the year. I hope tojoin you at the earliest convenient opportunity.

I recommend myself veryhumbly to your gracious consideration, and pray God to grant you,gentlemen, a happy and long life. From Montaigne, this 8th February 1585.Your humble brother and servant, MONTAIGNE. XI.——To the same.GENTLEMEN,—I have here received news of you from M. Iwill not spare either my life or anything else for your service, and willleave it to your judgment whether the assistance I might be able to renderby my presence at the forthcoming election, would be worth the risk Ishould run by going into the town, seeing the bad state it is in, —Thisrefers to the plague then raging, and which carried off 14,000 persons atBordeaux.—particularly for people coming away from so fine an airas this is where I am. I will draw as near to you on Wednesday as I can,that is, to Feuillas, if the malady has not reached that place, where, asI write to M. De la Molte, I shall be very pleased to have the honour ofseeing one of you to take your directions, and relieve myself of thecredentials which M. Le Marechal will give me for you all: commendingmyself hereupon humbly to your good grace, and praying God to grant you,gentlemen, long and happy life.

At Libourne, this 30th of July 1585. Yourhumble servant and brother, MONTAIGNE. XII.—“According to Dr. Payen, this letter belongs to 1588.

Itsauthenticity has been called in question; but wrongly, in our opinion. See‘Documents inedits’, 1847, p.

12.”—Note in ‘Essais’,ed. Paris, 1854, iv. It does not appear to whom the letter wasaddressed.MONSEIGNEUR,—You have heard of our baggage being taken from us underour eyes in the forest of Villebois: then, after a good deal of discussionand delay, of the capture being pronounced illegal by the Prince. We darednot, however, proceed on our way, from an uncertainty as to the safety ofour persons, which should have been clearly expressed on our passports.The League has done this, M. De Barrant and M. De la Rochefocault; thestorm has burst on me, who had my money in my box.

I have recovered noneof it, and most of my papers and cash—The French word is hardes,which St. John renders things.

But compare Chambers’s “DomesticAnnals of Scotland,” 2d ed. 48.—remain in theirpossession. I have not seen the Prince.

Fifty were lost. As for theCount of Thorigny, he lost some ver plate and a few articles of clothing.He diverged from his route to pay a visit to the mourning ladies atMontresor, where are the remains of his two brothers and his grandmother,and came to us again in this town, whence we shall resume our journeyshortly.

The journey to Normandy is postponed. The King has despatched MM.De Bellieure and de la Guiche to M. De Guise to summon him to court; weshall be there on Thursday.From Orleans, this 16th of February, in the morning 1588-9?.—Yourvery humble servant, MONTAIGNE. XIII.——To Mademoiselle PAULMIER.—This letter, at the time of the publication of the variorumedition of 1854, appears to have been in private hands.

P.382.MADEMOISELLE,—My friends know that, from the first moment of ouracquaintance, I have destined a copy of my book for you; for I feel thatyou have done it much honour. The courtesy of M. Paulmier would deprive meof the pleasure of giving it to you now, for he has obliged me since agreat deal beyond the worth of my book. You will accept it then, if youplease, as having been yours before I owed it to you, and will confer onme the favour of loving it, whether for its own sake or for mine; and Iwill keep my debt to M.

Paulmier undischarged, that I may requite him, ifI have at some other time the means of serving him.